The Nature Corner: Healing

Published 11:14 am Sunday, February 7, 2021

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

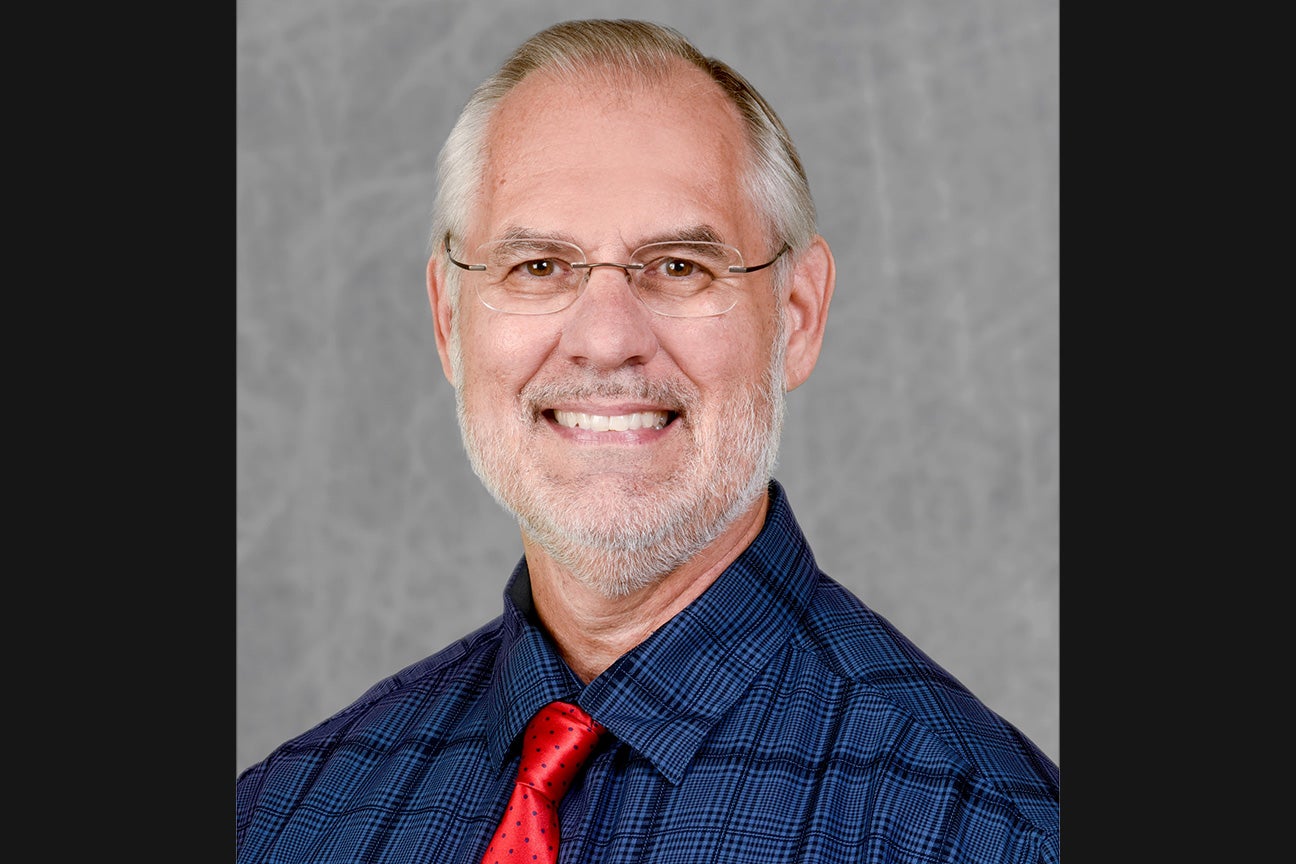

By Ernie Marshall

Since we have recently inaugurated the 46th President of the United States, it seems appropriate to reflect, regardless of our party affiliation or loyalty, on the political turmoil of the last four years or so, and healing the wounds inflicted on and by us.

I cannot think of a better way of doing this than considering the relationship between John Adams (1735-1826) and Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826). This relationship originated in their friendship as compatriots in the American Revolutionary War, degenerated into rivalry and vicious hostility beginning with Adams’ presidency and finally their fond friendship was restored during their years after retiring from political life.

It is a bit of a reach back to the beginning days of our republic over two hundred years ago, but it can offer badly needed perspective. If Adams and Jefferson could do it, by golly, so can we.

We should begin by quelling the notion that those times were so culturally and politically different that a comparison with ours cannot be helpful. But as the French proverb goes, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

First of all, if you dig deeper than current disputes over gay marriage, abortion, etc., to philosophical bedrock, many of the issues are much the same. The parties that emerged under Adams and Jefferson, the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, were at odds over the powers to be invested in a central or federal government. The federal government created in 1787 at the Constitutional Convention required huge compromises between those that were loath to relinquish individual rights and regional sovereignty and those favoring a strong federal government. Sound familiar?

Secondly, the contention between the competing political parties that emerged then were at least as heated as today, with plenty of mudslinging and character assassination. Present-day Republicans may have their voice in Fox News, and Democrats perhaps in CNN or MSNBC, but Jefferson’s platform was the National Gazette, and Alexander Hamilton’s (the leader of the Federalists) the Gazette of the United States. Here is just a sample. The Federalists called Jefferson “a mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.” The Anti-Federalists attacked Adams as a “hideous hermaphroditical character, with neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

Thirdly, the cultural differences between Adams and Jefferson were not so different from perceived differences between today’s Democrats and Republicans. Adams was a Harvard-educated lawyer from Massachusetts, living most of his life in Boston. Jefferson was born into a successful farming family in Virginia’s Albemarle County. (Jefferson, by the way, attended William and Mary College in Williamsburg, the colonial capital of Virginia, and was also educated as a lawyer.) They therefore contrast as urban versus agrarian and northern versus southern, as well as in their political/philosophical viewpoints.

Adams and Jefferson worked tirelessly and shoulder to shoulder throughout the revolutionary period, from its raw and raucous beginnings, through the creation of the Articles of Confederation and the work of the Continental Congress, and the writing of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. It was primarily Adams who pushed for Jefferson being the author of the Declaration of Independence, saying Jefferson had a better pen than he — and everybody else I would add.

Adams’ character and accomplishments are lesser known than Jefferson’s, so I mention one that says much about the man. He was the lawyer who defended Captain Preston and the other British soldiers who fired on the rowdy mob of colonists at the Boston Massacre. The mob was threatening and taunting the soldiers and throwing at them stones, snowballs and whatever came to hand. Someone shouted “fire” — probably someone in the mob or a bystander — and some soldiers let loose with a volley of musket fire. A familiar scene and emotional issue? At what point does law enforcement resort to deadly force?

Adams’ brilliant summation to the jury lasted over a day, and the jury came back with a verdict in two and a half hours. All six of the soldiers were found not guilty. Among other things, the trial perhaps established the principles of “innocent until proven guilty” and “reasonable doubt.”

This, of course, was not a popular outcome, and Adams knew he was risking his career, perhaps his own safety. But many recognized Adams’ moral courage and the importance of this incipient shining Republic setting an example of “justice for all.”

The friction between Adams and Jefferson began when Adams narrowly defeated Jefferson for the presidency in 1796. According to a quirk in current election laws, even though Adams and Jefferson had by then formed opposite political affiliations, Adams became president and Jefferson vice president, Adams receiving the most electoral votes and Jefferson a close second. (Imagine, if you will, if we had that same arrangement now, Biden would be president and Trump his vice president.)

So the situation was tense from the start, but heated up with the Alien and Sedition Acts under Adams’ presidency. France and Britain had been at war since 1793 and in 1796 the French began raiding and seizing American merchant ships to England. The Alien Act restricted immigration from abroad, limited immigrants’ acquisition of citizenship and increased their deportations and arrests.

This disturbed Jefferson, having a more favorable view of France than did the Federalists, but the Sedition Act infuriated Jefferson, the champion of first amendment rights. The Sedition Act clamped down, including fine and imprisonment, on freedom of assembly, speech and the press when criticizing the Federalist administration.

In Adams’ favor it should be said that America feared war with France. Different political viewpoints strike the balance differently between national security and human rights.

Adams was defeated in the presidential election of 1800 by Jefferson, who served two terms. After this, Adams went back to his law practice and Jefferson to Monticello. (This was back when politicians didn’t make a career of politics, but returned to a citizen’s life.)

Adams and Jefferson went on to exchange letters that reminisced about their days as patriots and brothers in arms, discussed religion and philosophy and, yes, discussed their grandchildren. Old wounds healed with time, their deep friendship was regained.

This June 4, 1804 letter to John Wayne Eppes by Jefferson regarding Adams captures well their mutual good feelings: “He and myself have gone through so many scenes together, that all his qualities have been proved to me, and I know him to possess so many good ones, so that I have never withdrawn my esteem . . .”

Both men died on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Adams’ last words were “Thomas Jefferson still lives.” Unbeknownst to him, Jefferson had died a few hours earlier. Two friends dying in each other’s spiritual embrace.

Ernie Marshall taught at East Carolina College for thirty-two years and had a home in Hyde County near Swan Quarter. He has done extensive volunteer work at the Mattamuskeet, Pocosin Lakes and Swan Quarter refuges and was chief script writer for wildlife documentaries by STRS Productions on the coastal U.S. National Wildlife Refuges, mostly located on the Outer Banks. Questions or comments? Contact the author at marshalle1922@gmail.com.

FOR MORE COLUMNS AND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR, CHECK OUT OUR OPINION SECTION HERE.