The Nature Corner: Why don’t . . .

Published 7:54 am Friday, April 15, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

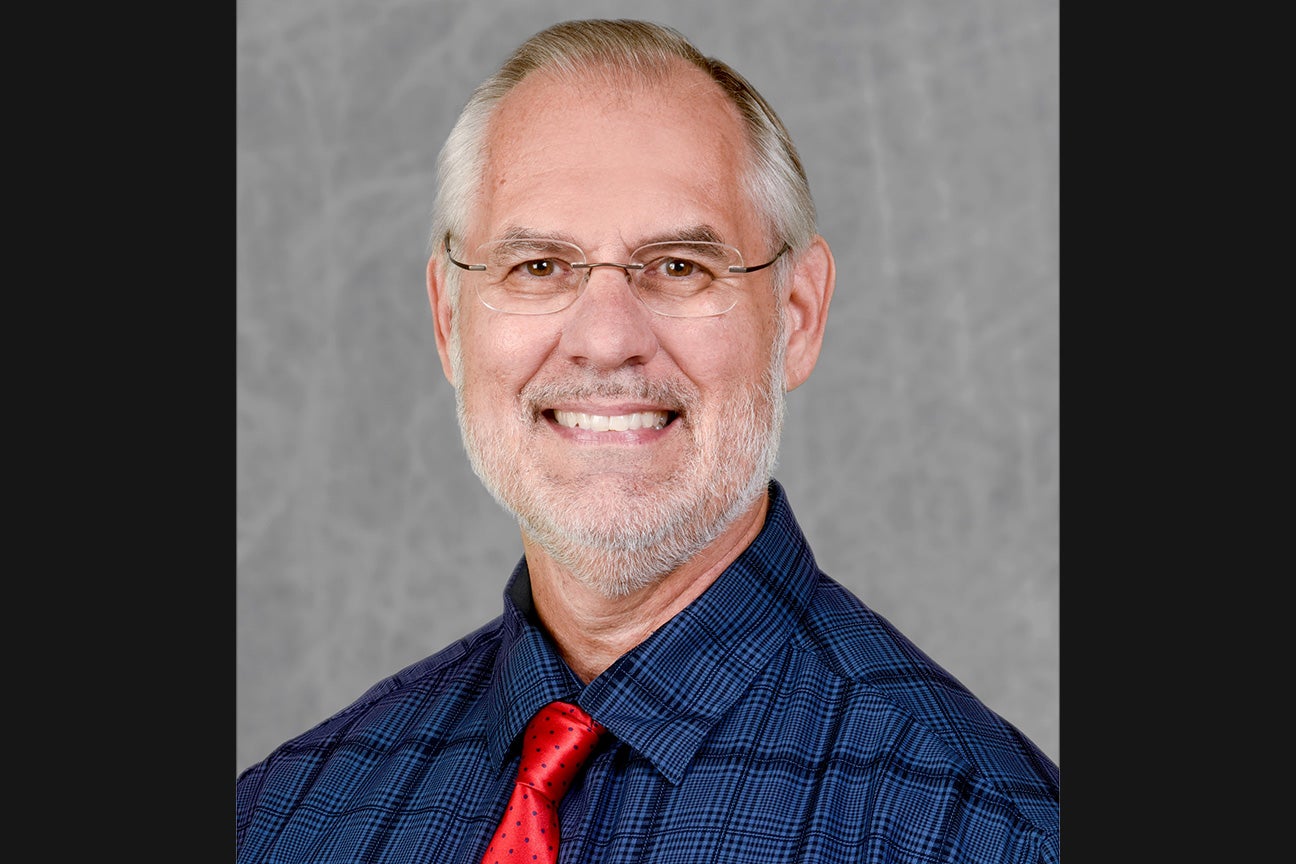

By Ernie Marshall

Nature presents a number of oddities, contraries of sorts. Let us look at a few.

Why don’t snakes have legs?

The Biblical explanation from the Book of Genesis Chapter 3 is that the serpent that tempted Adam and Eve to eat the forbidden fruit was cursed by God to forever crawl on its belly.

The answer from evolutionary biology goes a bit differently, but is still burdened with questions. This sort of thing has been termed “regressive evolution.” Indeed, it appears that nature is moving backwards, to a time before amphibians appeared, adapted to walking upon land rather than living in water. Snakes were a rather late product of reptile evolution, finding an unorthodox niche for themselves. Snakes have several methods of locomotion but a common one has, I think, a curious resemblance to how a fish swims. The next time you see a snake moving on the ground, let your curiosity win out over your nervousness. It seems to move by pushing against irregularities on its surface, to propel itself forward. A fish, in a different way, has both a side to side and forward motion. I played a game with first graders once where they were to mimic how different animals get about. When it came to snakes, most resorted to slithering on the floor in a rather serpentine fashion.

But snakes — and humans? — pay a price for living crawling on their bellies. Maybe that is how we got venomous species. The snake follows the scent of what it has bitten until it dies then swallows it whole.

No wonder snakes give most folks the creeps.

Why don’t some birds fly?

Why win nature’s lottery, be able to fly away from your enemy’s grasp, soar over mountain peaks, then give it all away? Nature is frugal, sparing in creating the special anatomy and physiology that flight requires. Hence birds that evolve in environments free of predators and abundant in food sources have no need of flight and seem to follow the rule of “use it or lose it.” The case of the flightless and almost wingless dodo was considered in a recent column. Some of these flightless birds became quite large. The moa of New Zealand stood 10 feet tall, a couple of feet taller than the African ostrich, the largest of extant flightless birds. The elephant bird of the island of Madagascar was another flightless avian giant of the past. Legends were told that it could fly to its nest with an elephant in its talons to feed its young. Gigantism and flightlessness went together. A bird with a wingspan of over 10 feet, such as with an eagle or condor, would be too large to master the physics of flight. These flightless birds typically evolved on islands, protected by surrounding ocean from land predators.

Why don’t bats fly during daylight?

The difference between nocturnal (active after dark) and diurnal (active in the daylight hours) is familiar enough (the term “crepuscular,” active during the twilight of dawn and dusk, less familiar). Owls, for example, are well adapted to hunting at night by extremely sensitive sight and hearing. Bats, however, find and capture night flying insects by using echolocation. Working on the same principle as radar, they emit rapid, high pitched (beyond the range of human hearing) sounds that bounce off objects. The returning “echo” tells the bat what and where it is. There is a tropical fish-eating bat that uses the same method, locating fish near the water’s surface, then swooping down to snag it in its claws, osprey-fashion. There are also unusual bat varieties – such as so-called “flying foxes” – that eat fruit, bats that feed on and pollinate night-blooming flowers and vampire bats living exclusively on blood. They find a vein on a sleeping cow or deer, for example, slice it open with their razor-sharp teeth and lap up the blood that flows. They live in the Latin American tropics and coincidentally have no connection with the Dracula legends originating in Eastern Europe.

Why don’t most marsupials live elsewhere other than Australia?

There are some 250 species of marsupials, the great majority of which are native to the “land down under.” By contrast, in North America we have but one marsupial species, the Virginia opossum.

Marsupials are unique in that most of the development of a marsupial’s fetus takes place outside womb and in a “pouch” on the female’s abdomen. After being born, the young crawl from the birth canal to the pouch, where it latches on to a nipple to feed and grow.

To shorten a long tale for the telling, 125 million years ago marsupials “split off” from placental mammals at about the same time as Australia “split off” from Asia and became an island continent to go its own way in producing an astonishing array of marsupial species. Placental mammals, such as humans, have a temporary “organ” that allows for the exchange of fluids, including nutrients, between mother and fetus during gestation and a more developed animal at birth. This was an advance over fetal development in marsupials.

All the moving about with drifting land masses and arising of land bridges makes for an interesting distribution of Earth’s flora and fauna, including the eventual homecoming of the Outer Banks horses, after evolving on this continent millions of years before.

Why don’t all animals walk on four legs?

The flightless birds mentioned above are bipedal, so birds do whatever walking, running or hopping on two legs because their forelegs became wings for flight. Humans and a few other primates are the only group of animals that went the way not walking on all four legs. In the case of humans and their ancestors, their forelimbs became modified for making and using tools – spearheads and such – for hunting. This was nature’s great experiment that led to a species with culture and technology, including hands that can hold everything from Van Gogh’s paintbrush to John Dillinger’s Thompson submachine gun. What twists and turns nature’s lengthy path doth take.

Ernie Marshall taught at East Carolina College for thirty-two years and had a home in Hyde County near Swan Quarter. He has done extensive volunteer work at the Mattamuskeet, Pocosin Lakes and Swan Quarter refuges and was chief script writer for wildlife documentaries by STRS Productions on the coastal U.S. National Wildlife Refuges, mostly located on the Outer Banks. Questions or comments? Contact the author at marshalle1922@gmail.com.

READ ABOUT NEWS AND EVENTS HERE.