Roanoke Island’s Mother Vine rooted in history

Published 5:11 pm Tuesday, November 15, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

If the Mother Vine could talk, she would tell you a long, long story.

A story of birth and growth, running wild and free in the sunshine along the banks of Roanoke Island. She could tell you of the arrival of a strange new people on the shores, followed by cultivation on a tall and unusual trellis. It stretched her branches and forced her vines to grow strong and sturdy. It was uncomfortable at first, but her sweet fragrant grapes produced in abundance and she soon learned to be content in her new supports.

Her roots reached down, down into the sandy earth, growing thick, swirling and twisting together. Her branches covered over an acre of lush land. When ferocious winds would come to the island, battering her branches and hurling her fruit across the island, she endured.

That’s really one of the only things we know for certain about the Mother Vine – she has endured.

No doubt the Native Americans enjoyed the sweet Scuppernong grape, a variety of the Muscadine family that is native to North Carolina, as a raw fruit or perhaps made into wine.

When the early explorers Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe arrived in 1584, they eloquently observed that the area was “so full of grapes, as the very beating and surge of the Sea overflowed them.”

Some say the earliest English colonists cultivated the Mother Vine because of the tall English-style trellising – built like a canopy rather than in rows like modern vineyards. Perhaps they did, or perhaps it was others who came later who coaxed the large white grapes from the Mother Vine.

In the early 1700s, Peter Baum, a vintner from New Bern, received a land grant from England for tract of land that we know as Mother Vineyard. Baum’s descendants report that the trunks of the Mother Vine were big and old from their earliest memories.

In 1891, the Roanoke News out of Weldon, NJ stated that, “The largest scuppernong vine in the world grew on Roanoke Island and covered more than one acre of ground. It was found there by Sir Walter Raleigh in 1585 and was living and thriving until a very few years ago. It is believed to be the parent stem from which all others sprung.”

It’s unclear if the information was inaccurate or if the Mother Vine did indeed wane some in the late 1800s. Other vineyards were planted in the nearby for winemaking. Over the years, development overtook those vineyards until only the ancient vine remained, though it dwindled to about a half an acre.

In 1957, John and Estelle Wilson purchased the Mother Vine property and cared for the vine for the remainder of their lives, appreciating its history and seeking to share it.

“That was the wish of my mom,” said their son John Wilson IV, former Manteo mayor, who inherited the property after his parents passed away. “She wanted dogs and children to always have access to Roanoke Sound at Mother Vineyard because throughout her childhood, and all the way through mine, that was where all children rode their bikes, walked their dogs, and went swimming.”

Wilson is in the process of turning the property on which the vine sits over to the Outer Banks Conservationists (OBC), a non-profit that manages Island Farm and Currituck Beach Lighthouse. “Our whole intent, of course, is to make Outer Banks history accessible and open to the public,” said executive director Ladd Bayliss. “My main goal is to make sure they’re always available to the public in perpetuity, and we’ve made great strides to make sure that’s the future of this.”

Transferring ownership to OBC will ensure that the Mother Vine continues to be protected and available for the public to enjoy. Though the home on the vineyard property is rented and visitors are asked to be courteous to this fact, the public is invited to stroll through the grounds to explore the vine, or walk down to the sound beach from the small parking area on Mother Vineyard Road.

When asked who takes care of the vine, Wilson, looking at Ladd and local author and Mother Vineyard resident Angel Khoury, said, “We all do.”

“It’s unusual that you can have something that’s historical – that’s alive – that’s that old. We don’t even have many buildings that are that old … But to have a living thing that’s that old, it has to be preserved, has to be cared for. Maybe even more so than buildings. Because you can rebuild an old building. But a living thing? You can’t just instantly make another 400-year-old grapevine, right? If it’s gone, it’s gone,” Khoury said.

The vine is a community treasure, and it is looked after primarily by neighbors. Once a year it is inspected by a vintner from Duplin County, but contrary to common belief, the Mother Vine doesn’t take a lot of work to maintain.

Unlike the long-gone vineyards in the area that were planted for a high production for winemaking, “The old mother just sat there for all these hundreds of years and didn’t require much attention. Some years she has lots and lots of grapes and other years she has very few because we don’t know what we’re doing,” Wilson laughed. “We just keep it going, and we protect her from development.”

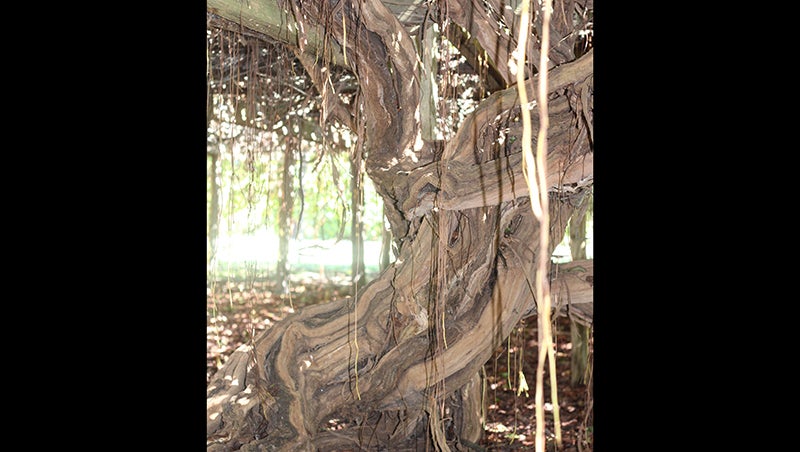

According to Wilson, the vine atrophies and drops new roots and “just keeps on going.” A peek under the arbor reveals a world vaguely akin to Stranger Things. Hundreds of tendrils drop from the canopy of the Mother Vine, providing support and photosynthesis for the plant. Wilson said that every decade or so, one of the tendrils will sink into the ground and a new root will emerge.

Crouching beneath the branches, it’s easy to spot the primary ancient root. It is a massive and twisted collection of wood in the center of the vineyard. A piece of artwork, really. The great root brings to mind a deeply lined face, showing years of living and loving and heartache. There’s beauty in that face that endures beyond youth; it’s a beauty of age and wisdom.

There are several smaller roots in the vineyard. It produces in August or September. In Wilson’s lifetime, the fruit of Mother Vine has been picked mostly for community enjoyment.

The grapes are picked by people who stop in to visit the mighty vine, or by children who ride by on their bicycles. Over the years, if the crop is good, neighbors may make little jars of scuppernong grape jelly to share.

The grapes aren’t sold, unless, Wilson said, “the little boy across the street maybe sells them.” He recalled, “… It reminded me of being five years old and doing exactly the same – picking grapes and selling them on the side of the road so I could go to Mr. Moncie’s five and dime and buy something.”

For Wilson, the Mother Vine is deeply engrained in his childhood. Though the Mother Vine herself does not produce grapes for wine, she does have “children” vineyards that came from her cuttings. Scuppernong wine, made by Duplin Winery, tastes – according to Wilson and Khoury – just like the grapes picked fresh off the vine.

“It smells like Roanoke Island summer childhood,” Wilson said, as he placed a dessert wine glass on the table in front of me. The table was strewn with newspaper clippings, historical brochures and old photos of the Mother Vine. In a moment, with a sip of the distinctively sweet wine, the old papers were imbibed with life and flavor and sweetness.

If the Mother Vine could talk, she would tell 10,000 stories. Though she’s kept most of these stories to herself deep within her centuries-old roots, the stories are continuing to be written on Roanoke Island through new people and experiences.

“For those of us who grew up here,” Wilson concluded, “The Mother Vineyard is just another small part of the extraordinary history of Roanoke Island.”

SUBSCRIBE TO THE COASTLAND TIMES TODAY!